The Objectivity of Architecture

Last week, I had a meeting with a supplier to present an architectural blueprint I had prepared, with the goal of assessing whether their system could support it.

After a brief presentation, we moved into a bilateral discussion. A young engineer on their side challenged my assumptions, and within fifteen minutes I was convinced he was right. I had to revise — fortunately not radically — the processes and integrations I had originally envisioned.

When I openly acknowledged that he was right, both the supplier’s team and my own colleagues seemed genuinely surprised. Some even tried, half-jokingly, to talk me out of changing my original design, like if the young engineer acted in disrespect. In that moment, I had another realization: many people take it for granted that an Architect should possess complete knowledge of everything within the scope of the architecture they design — to the point of defying the internal logic of systems themselves and arrogantly imposing a personal vision on top of reality.

I firmly believe that an Architect who works this way is preparing for disaster. If you do not study the terrain, understand the materials, or acknowledge the skills of the people involved, you are not designing an architecture — you are performing a vanity exercise. And vanity-driven architectures eventually collapse, causing harm to others and often significant financial damage.

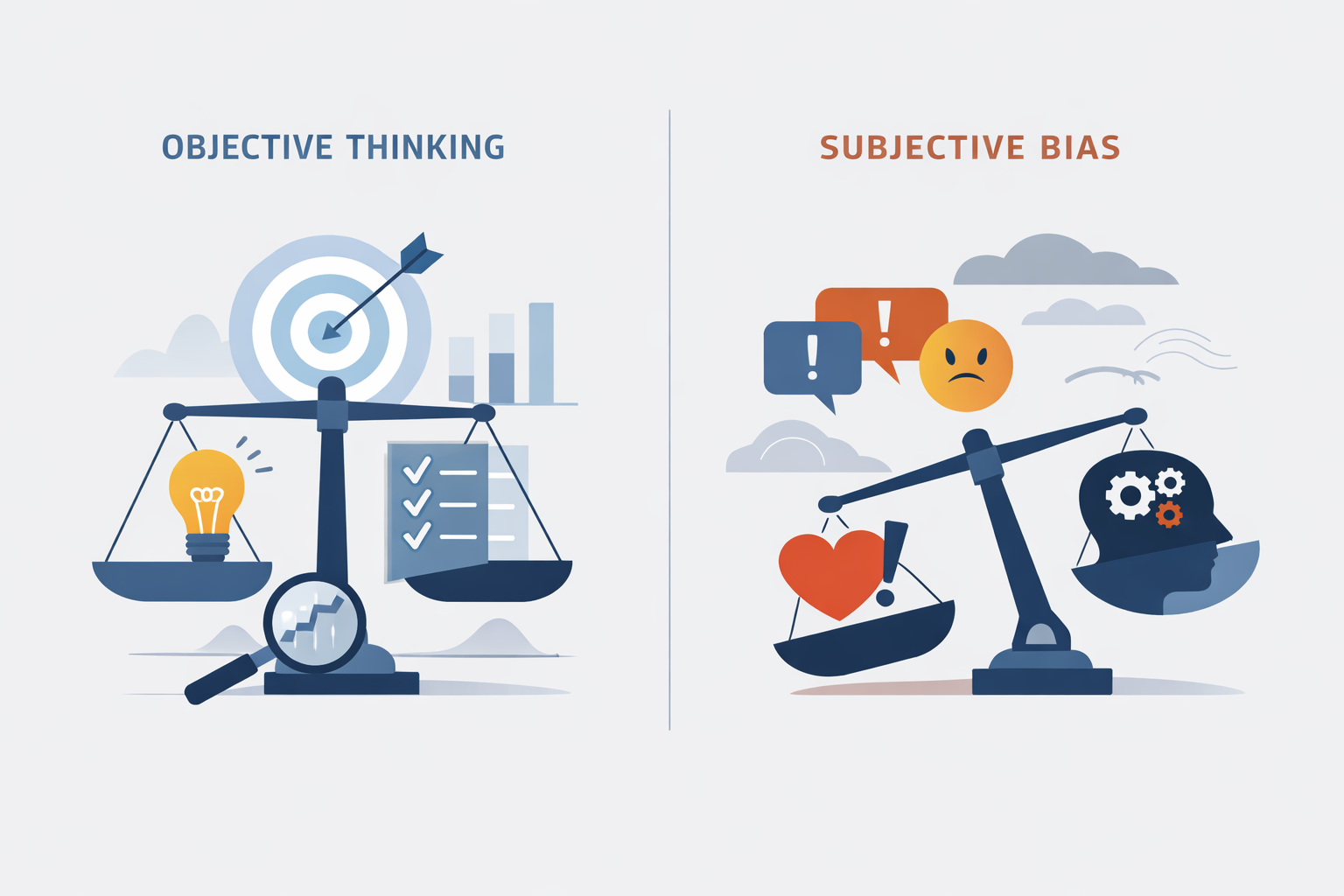

For some, being an Architect is reduced to a symbolic milestone in career progression: a title to wield against others, a perceived badge of superiority, perhaps even a justification for a higher salary. (I can personally debunk that myth—I have been an Enterprise Architect while earning less than several senior developers.) The real cost of this mindset, however, is the gradual loss of objectivity and rational thinking.

This reminds me of a situation where I had a prolonged conflict with a colleague. We argued for weeks, exchanged harsh emails, and strongly disagreed on many issues. Yet, during a public architectural discussion, I openly defended his position on a topic where I believed he was right. Later, he reached out privately to thank me for being objective and for not letting personal differences interfere. That reaction surprised me—almost as if objectivity were optional, even when the alternative could risk hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in damages. Silencing one’s ego is difficult, in architecture as in any other discipline, but the psychological effort pays off in the long run.

One aspect that is often misunderstood from the outside is that an Architect is not a Subject Matter Expert. Architects are not expected to know everything about every system, technology, process, or organizational nuance within the scope of their architecture. Sometimes, even Architects themselves forget this, falling into the trap of believing they can independently interpret business, legal, technical, and organizational concerns without relying on experts in those domains.

Naturally, everyone brings personal interests and professional or academic backgrounds that lead to deeper knowledge in certain areas. But an Architect must remain acutely aware of the limits of their expertise—and be humble enough to listen, learn, and integrate the insights of true experts. Objectivity in architecture is not about knowing everything; it is about knowing how to synthesize reality, evidence, and expertise into coherent and sustainable decisions.