Self-Sustainable DevOps

Teams and Services

One of the most foundational elements in Enterprise Architecture is the definition of Application Services (to be distinguished from the Business Services), that represent the IT implementations supporting the Value Streams of the enterprise: clear scopes, boundaries and functions are crucial for the best efficiency of the organization.

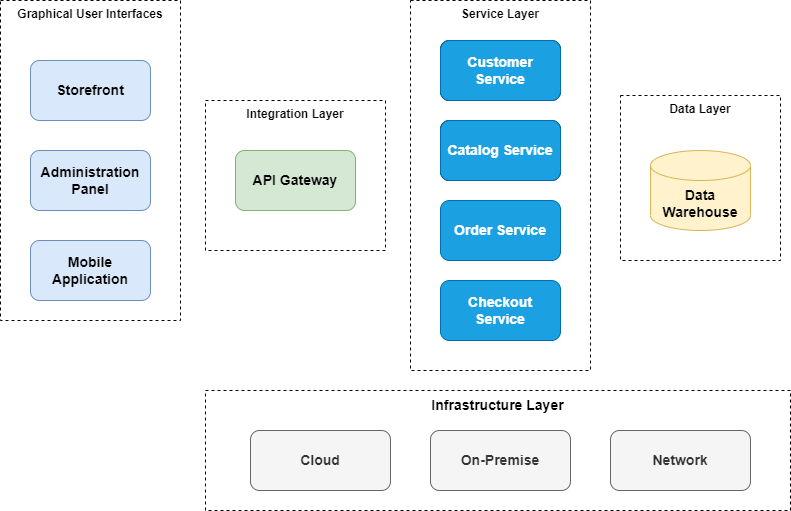

Considering the architecture of a stereotypical (bare-bone simple) e-Commerce system produced by an organization, represented in the following graph

In the Service Layer of the architecture we can observe the presence of four core services (with their scopes):

- Customer Service - Masters the information and processes for the management of customers

- Catalog Service - Provides the functions to manage catalog of products

- Order Service - Enables customers to place products in baskets and proceed to the ordering and provisioning

- Checkout Service - Allows customers to pay for the products thy are wishing to acquire

They might have been implemented by one single person (hopefully not!), one single team, or by several teams (collectively or individually), and they likely integrate each others through internal interfaces, behind the public API Gateway stereotype, to move information between themselves, as needed.

The popular Team Topologies methodology assigns design, implementation and operations responsibilities over systems and services to teams, according to their orientation (as Stream-Aligned Teams, Platform Teams, Enabling Teams and Complicated Sub-system Teams), so that they can own a certain area of interest and collaborate with each other, producing coherent and consistent products for the enterprise.

This organizational methodology emerges from the well-known Conway’s Law, that states

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure

In fact the focus on the communication and collaboration of teams within an enterprise is crucial for producing valuable and consistent outcomes, and such problem has been considered with several approaches.

Service Interfaces

One of the neglected aspects by teams owning an entire system (eg. The e-Commerce System) or a single application service (eg. The Catalog Service of the e-Commerce System), is the consideration that this artifact (system or service) will be consumed by others, through a programmatic perspective.

When working on Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) a lot of effort is employed to do research on the user behaviors, mocking targets and producing graphical elements, since the identification of a clear persona as a user of a system, that activates one or more services with its interactions through those interfaces (eg. Selecting an item from the catalog, Checkout and paying for the items in the basket, Reviewing past orders and accounting, etc.): this is easily translated into user stories, bending mostly towards the product ownership, with commercial orientation.

Anyway, I have witnessed in several occasions that the design of the integration interfaces (eg. REST APIs, gRPC services, GraphQL, etc.) is neglected, as if those interfaces were less important, while in fact they represent the way a component of an enterprise architecture communicates with another component: since the typical orientation towards commercial deliverables, architectural concerns (application interfaces are in fact architecture artifacts) are lowered in regards.

I would like now to clarify the ‘API’ acronym, used and abused within organizations, but obscure in its meaning to many non-technical functions, by quoting the definition that Martin Reddy provides

An application programming interface (API) is a way for two or more computer programs to communicate with each other. It is a type of software interface, offering a service to other pieces of software

As it is easy to extrapolate from the above definition, APIs are indeed interfaces that allow two applications to communicate between themselves and therefore they (the applications) are the main actors in play, but the real interested ones in consuming those APIs are in fact the developers who write code for their software solutions to consume those interfaces, once the software is compiled and runs (as an application service): in such context, a well-designed REST API provides an elegant and easy way to perform one or many mutations to the information (eg. create, update or delete) or the query of the most valuable information (eg. paginated queries)

I have observed that the reason why API design is neglected can be many times tracked down to the lack of service design knowledge from within the team producing the components (for example, the appointed architect has no preparation on the theoretical elements), or from a lack of domain knowledge about the service to be provided, or ultimately by a too large bounded context assigned to the service (that tracks back to the lack of service design knowledge).

The Proliferation of Clients

Regardless of the elegance, clarity and availability of the interfaces to applications, a typical scenario in large organizations is the one of teams providing a simple documentation, in the form of wiki pages, PDF documents, chat history, to assist the teams interested in integrating those applications, shifting the responsibility of producing the client code to the consumer.

In this self-service scenario, I have observed quite a variety of approaches, from the very bad ones (the list is very long and I must omit it for brevity) to more virtue examples (such as using external tooling to generate clients): in any case, this approach causes a proliferation of implementations of clients, that increases the uncertainty within the organization, since none wants to re-invent the wheel (with all that this means) writing yet another client to the service, while at the same time missing functions from the ad-hoc implementations might be missing.

Truth to be told, such bad approach is not just adopted for internal integrations, and small-to-large provider of services neglect providing their own customers a true interpretation of the access to their services, fostering the proliferation in the public repositories (Nuget, NPM, etc.) of custom implementations: I contributed to such scenario, since some large providers were not shipping a given client for .NET and I found myself in need to produce it, and then share it as an open-source library.

Standards at the Rescue of DevOps

In our current landscape of the IT industry (all-in-all cross-cutting considered), the ownership and leadership of development processes, in the vast majority of cases, doesn’t require anymore the screening for the knowledge of specific theoretical elements of software engineering, given the scarcity of resources in the market, but also given the need of deploying fast (from MVP to MVP), that produces bastard effects in the adoption of authoritative standards, which are employed only partially or with little consideration of their benefits.

Considering the integration interfaces artifacts, standards like OpenAPI or GraphQL are used to align the efforts of the IT industry segments producing services and tooling, to ease the collaboration, governance and overall experience: for example, .NET libraries like Swashbuckle help with the generation of OpenAPI documents describing a service set of operations, and applications like AutoRest can interpret that generated standard and produce Java, Python, .NET or JavaScript client libraries, that interested consumers can easily integrate in their projects.

In such a process, the team responsible of producing and operating a service can produce an authentic version of the client libraries for the consumers, reducing or eliminating the risk of proliferation of insecure alternatives, produced sometimes with a non consistent design or a narrow scope.

Providers of services, like Microsoft Azure, include in their DevOps process the generation and publication of both the standard specification of the services offered, and the generated language-specific client libraries, to reduce or eliminate the risk of integration: in fact, the above mentioned AutoRest application implementation was originated from this need.

Consumer Scenarios

The contrary of the virtue process described above, as many of you will recognize being the real state of things within a typical organization, is that teams responsible of producing a service, which need the integration of other services (within or without the same organization), not finding available client libraries for that specific service, are then forced to manually produce them, typically focusing on the parts of the integrated service relevant to their business, and therefore hardly reusable by other teams.

This approach causes a proliferation of integrations, creating insecurity (which library should I use?), distracting time and efforts by teams external from the integrated service in the maintenance of those artifacts, resulting in tensions at several levels of the organization.