The Microservices Dilemma

Since few years now the hype of the microservices architecture is growing and growing. It is a popular architecture for building distributed applications, separating and isolating the technologies needed to implement domain-driven services, such as they can be developed, deployed and scaled independently by one or more teams. But how they differ from a traditional SOA?

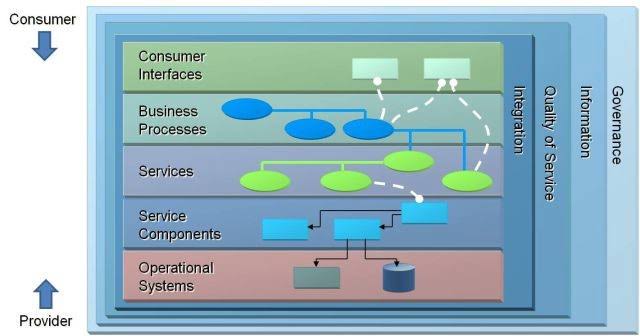

The Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) Pattern

The Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) is an architectural style that defines the use of services to support the requirements of software users. A service is a self-contained unit of functionality, such as retrieving an online bank statement: by that definition, a service is a discrete unit of functionality that can be accessed remotely and acted upon and updated independently, such as retrieving a credit card statement online.

Such a model has been used for several years in the enterprise world, but it has been often misused and misunderstood. The SOA is not a technology, but an architectural style, and it is not a silver bullet for all the problems of the enterprise world. It is a way to design and implement software systems that are loosely coupled, interoperable, and reusable.

According to the pattern, a system, or even an entire enterprise, can be composed by integrating several external services, which provide each a portion of the information and the functions needed to implement a business process. The services can be implemented using different technologies and can be deployed on different platforms, but they must be able to communicate with each other using a common communication protocol.

Nothing unknown to almost all of you who are reading until now.

The Microservices Pattern

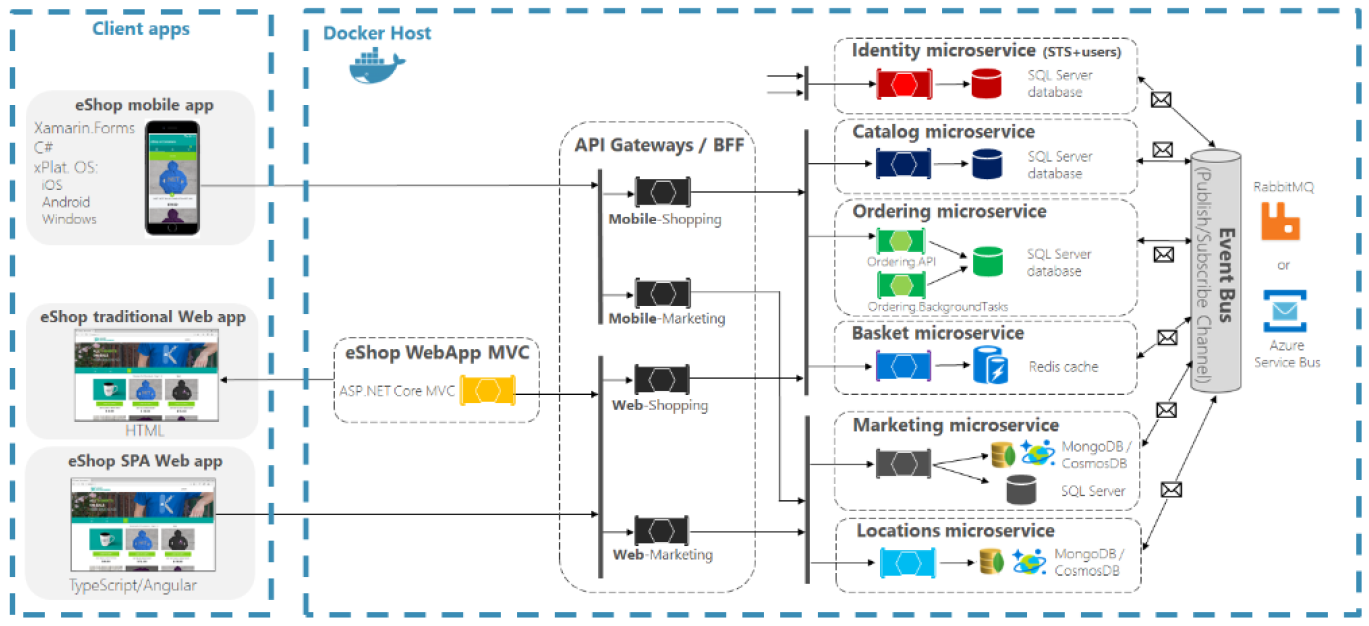

Copyright © 2018 Microsoft - Designing and implementing API Gateways with Ocelot in .NET Core containers and microservices architectures

Copyright © 2018 Microsoft - Designing and implementing API Gateways with Ocelot in .NET Core containers and microservices architectures

The terminology “Microservice” first appeared in 2011, in a blog post by James Lewis and Martin Fowler, and it is a variant of the SOA architectural style. Summarizing the principles of the paper, the microservices architecture is a style of software architecture that has the following characteristics:

- The application is composed by several small services, each one running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API.

- Each service is built around business capabilities.

- Services are independently deployable.

- Services are independently scalable.

- Services can be implemented using different technologies.

- Services are owned by small teams.

As such, the overall ambition of the pattern is not to dictate any specific technology or solution for the implementation, but instead to provide a set of guidelines that can be used to design and implement a distributed application, focusing mostly on the concept of products, rather than projects, and enabling a greater agility in the development and deployment of the features.

The Evolution of the Microservices

Like many good ideas, the microservices architecture has been misused and misunderstood, and it has been often used as a synonym of distributed architecture, or distributed system, or service-oriented architecture. But the microservices architecture is not a synonym of any of these terms, and it is not a silver bullet for all the problems of the enterprise world.

In fact its adoption was helped by the emergence of technologies developed for the support of cloud-native applications, such as containers (eg. Docker), container orchestrators (eg. [Kubernetes]https://kubernetes.io), Service Fabric), and cloud platforms (eg. Azure, Google Cloud), which have been used to implement distributed applications, although they are not a requirement for the adoption of the pattern. Despite not being required, the majority of the IT practitioners implemented the microservices pattern by adopting a specific technological stack, heavily based on the Docker and Kubernetes components, with all its complexities and challenges, often without understanding the real orientation of the pattern.

Naturally, several of the critical aspects of a microservice architecture, such as the development and operational processes, the communication protocols, the data management, the security, and the monitoring, are not new, and they have been already addressed by the SOA architectural style, but the radical approach to define even smaller portions of a service domain, to be served independently, multiplied the complexity of the infrastructure needed to implement the pattern (service-specific databases, separated monitoring and alerting tools, multiple autonomous development and deployment processes), also to address the organizational change emerging from the philosophy of the pattern.

Containers, Orchestration, and Platforms

The adoption of containers, container orchestrators, and cloud platforms, has been a natural evolution of the microservices architecture, but it has been often misunderstood as a requirement for the adoption of the pattern. In fact, the microservices architecture can be implemented using any technology, and it can be deployed on any platform, but the adoption of these technologies can scale up the complexity for the development and deployment of the services.

Since the microservice is indeed a pattern, and not a specific technology, the architecture of a system might be respecting these principles through the adoption of provider-specific technologies (eg. Azure App Services, Amazon EC2 Instances, etc.), or even through the adoption of a monolithic architecture, where the services are implemented as libraries, and they are deployed as part of a single application: it is responsibility of an architect to define where the physical boundaries of a service are, and how to implement them.

Anyway, the usage of orchestration platforms to implement this pattern has been popularized by their alleged scalability and resilience, enhanced by the myth of cloud portability (the concept, never really achieved, of realizing an entire system resilient to the provider of cloud infrastructure, or even the on-premise provisioning), which instead turned up in practice to require more efforts to configure and maintain the infrastructure, to implement the services, and ultimately consisted of a parallel set of technologies to be learned and mastered.

Missed Business Opportunities

Some of the major arguments and drivers, from the business side of the IT, for the adoption of the microservices architecture, have been:

- Agility: the ability to develop and deploy new features faster, and to scale the services independently, without the need to coordinate the development and deployment of the entire system.

- Resilience: the ability to isolate the failures of a service, and to recover from them, without affecting the entire system.

- Scalability: the ability to scale the services independently, and to optimize the resources needed to run the system.

- Technology Independence: the ability to implement the services using different technologies, and to adopt the best technology for each service.

- Team Independence: the ability to assign a team to a service, and to let the team to develop and deploy the service independently.

- Business Independence: the ability to assign a business domain to a service, and to let the business to manage the service independently.

- Cost Reduction: the ability to reduce the costs of the infrastructure, and to optimize the resources needed to run the system.

- Cloud Portability: the ability to deploy the system on any cloud platform, and to migrate the system from one cloud platform to another.

As debated already in the previous paragraphs, some of these arguments have been proven by experience to be not so true, or at least not so easy to achieve, and the adoption of the pattern has been often driven by the hype of the technology, rather than by the real business needs.

In fact the hidden costs of setting up an organization that can handle a microservice architecture are often underestimated, and impact largely by surprise the business side of the IT, resulting in re-evaluation of plans, roadmaps, and budgets, and in the worst cases in the abandonment of the pattern, and the return to a monolithic architecture.

As much as from an IT Strategy standpoint the adoption of microservices can be a good choice, aimed to diversify the technology stack, opening to more opportunities in the market (people, technology vendors, cloud providers), the reality of the enterprise processes is to rely on a single set of technologies, skillset and vendors, to better forecast the costs and the risks of the business: such dynamics counters the arguments of Technology Independence and Cloud Portability, and it is often the reason for the failure of the adoption of the pattern.

Is It Worth It?

A couple of months ago (at the time I am writing this post), a team at Amazon made a lot of sensation in the industry, after the publication of an article titled Why Amazon Chose a Monolithic Architecture for Prime Video (and the related video), supporting the monolithic architecture of their new media service, that has been often used as a reference to argue the failure of the microservices architecture, and the superiority of the monolithic architecture.

Although this article has been a sort of relief for many architects and IT practitioners, frustrated by the development and operational challenges provided by the microservices architecture, including myself, I personally think that is too early to declare the failure of the pattern, and to return to the monolithic architecture for any kind of system.

Anyway, the pattern itself might still provide of high business value, independently from its technological implementation, especially in contexts of mixed technological stacks, such as in the cases of Merge & Acquisition, or in the cases of legacy systems, where the adoption of the pattern can be a good choice to modernize the system, and to open to new opportunities in the market.

One of the untold dynamics in the enterprise is indeed the primacy of the technology over the business, leading to weak positions of the business side of the IT, in favor of the development functions, who are more prone to experiment with new technologies, rather than to adopt the best technology for the business: to counter this dynamic, the business functions have over time introduced more and more agile processes aimed to involve developers into the decision making, and to align the technology with the business needs, but the reality is that the business is still often forced to adopt the technology chosen by the development functions, rather than the other way around.

What is a Microservice?

At the end of the day, I believe that the major misunderstanding of the microservices architecture is the definition of microservice itself, which is often confused with a service, or a component, or a library, or a module: the nature of the bounded context of the service is an unavoidable aspect of the pattern, and it is often overlooked, or misunderstood, leading to the implementation of a distributed monolith, rather than a distributed system.

In fact, several of the information and functions of a service are often shared with other services, and the boundaries of the service are often defined by the technology, rather than by the business domain, often leading to the re-implementation of the same existing functions, motivated by technological choices (communication efficiency within the same technology stack, modernization of the implementation), rather than by business needs.

It than becomes crucial to the successful implementation of the pattern to define the boundaries of the services, and to identify the business domains, and the business functions, that are the real drivers of the architecture, and to implement the services accordingly, rather than to follow the hype of the technology.